"Jazelle, focus please..."

The aforementioned phrase has become par for the course as of late in my fourth period Spanish II class. Working at a brand new charter school has offered me many opportunities and one of the best opportunities is the ability to have small, intimate classes. Jazelle is one of four students in my class and I have the ability to work closely with her on a daily basis. Well, I shouldn't say daily. Jazelle is frequently out due to unexcused absences, and because of this she often comes in only three days a week, if that. She has ability, but falls further and further behind because not only does she not make up work, but she also wastes valuable time when she is in class. Students like her bring to the forefront one of key educational issues of today: Grade retention.

Most of us have likely never been retained. Studies have shown that most students who are retained are minorities, English language learners, and tend to be male. We can all think back to someone in our past who was retained. Odds are that this person was the "cool guy" at the onset. This was the guy who could drive during his freshman year and the guy who bought the younger guys cigarettes as soon as he turned 18. We all initially worshiped this guy and many young ladies wanted to pursue a magical evening with him. However, once senior year came around and this guy was the super senior, well he wasn't as cool anymore. We could all drive ourselves and buy our own cigarettes and therefore this guy was no longer needed. As we wrote our college essays and began receiving college acceptance letters, we began to see this guy less and less. In fact, come to think about it, we really don't even know if this guy even made it to graduation.

Sound familiar? I know it does for me. It is inevitable that in a nation that strives to educate all its children that some children will not be properly educated. These students don't progress as society expects them to and yet we expected that somehow and some way they will magically do better the second time around, even though they proved they couldn't do it the first time. Think about it in terms of running a mile. You struggle, sweat, and gasp for air with your peers all the way to the end but fall just short of the finish and everyone else passes you and completes the distance. As you stand there, exhausted, your coach pats you on the back and says "Alrighty, didn't quite get there this time. Why don't you head back to the start and try it one more time the exact same way?" Sounds absurd, right? Yet this is exactly what we do when we retain students.

Having taught at an urban middle school, I have had seen many students be retained and I can tell you this: Retention did not work. The students who were retained were the worst behaved students I had. They knew their peers idolized them so they made it their business to entertain them, at the expense of the learning process. The problem was that many of these students had already thrown in the towel, even at the ripe old age of fourteen. They weren't good at school, didn't like school, and didn't care about any of it. Why did it even matter what grade they were in anyway? They were going to enjoy their last moments in public school by causing as much trouble as possible and hoping to get suspended so at least then they wouldn't be wasting their time in the school building. For these students, being retained did a lot more harm than good and it ended up hurting all parties involved.

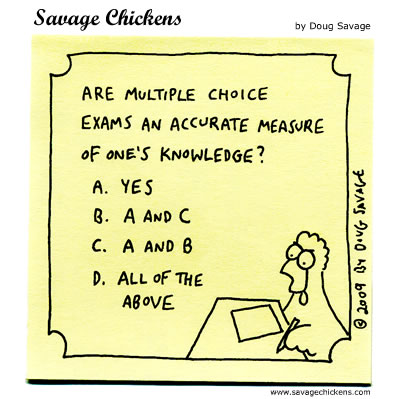

So the solution is obviously social promotion right? Well, I wouldn't say that is necessarily the case either. The truth is I am a concerned citizen. I'm worried about the future of this country, hence the title of my blog. I don't want to churn out high school graduates who can't read or write and yet that is exactly what we are doing. Do I really want someone with a fifth grade reading level to have as much political sway with their one vote as I do? Of course not. Yet, this is exactly where our country is headed because we are creating test factories where students cannot think on their feet. I, for one, do not think we should automatically promote a student who doesn't deserve it in an effort to keep him from being retained. So now this begs the question: If we don't retain him or promote him, what exactly do we do?

First and foremost, I think we need to re-analyze the very foundation of public schooling: The grade levels. Being out in southern California, I have begun to see an increasing trend of combination classes. For example, elementary schools often have class combinations such as 2-3 or 3-4. This to me makes perfect sense. If you are an advanced third grader, who says you shouldn't be in a class with a lower-level fourth grader? Teachers have a hard enough time differentiating in the classroom where we have multiple ability levels for our students. Imagine being able to cater your instruction, based on ability. I can see teachers reading this blog and just licking their chops at this possibility. After all, in college we take classes with all grade levels with freshmen and seniors often in the same classes. Last time I checked, nobody was arguing that freshman should only take classes with freshmen, sophomores should only takes classes with sophomores, etc. If this model works at the collegiate level, shouldn't it be implemented in the early grades as well?

But again, this makes too much sense and so this is why I am a lowly high school teacher and not the secretary of education (yet). As for me, I am stuck in a situation with Jazelle which forces me to decide if I should limit her life opportunities by retaining her, or jeopardize her future by sending out into a real world she is obviously unprepared for. If I pass her and all her other teachers fail her, have I done a lick of good? If I fail her and have her in my class again next year and she decides she'd rather be the class disruptor than even try to learn, have I done a lick of good? Is it this girl's fault she isn't good at school even though society expects it of her?

I don't know what I will end up doing with Jazelle. She acted the exact same way last semester. I had hoped that by giving her a passing grade, it would have lit a fire under her and given her a paucity of motivation. However, general apathy has quashed any potential fire that lies dormant inside of her. Begging and pleading do not work. Parental contact does not work. Vince Lombardi motivational speeches do not work. The glaring F on her progress report does not work. This is a girl who has given up on school and could care less about where she ends up in life. She is there everyday to kick it with her friends and if she has done that, then it has been a good day for her. As her teacher at the end of the day, it is up to me to determine if she has earned the right to advance to a further course of study. As of this very moment, I am at an impasse.

So are the rest of her teachers.